I’ve been struck by the number of Thanksgiving greetings I’ve gotten from my fellow Substack writers all day today. Mostly, I just want to reiterate to all of you what they’ve all said to me: thank you for supporting my work on Substack here at Howlin’ at the Moon in ii-V-I. Thanks to your generosity, I’m actually able to pay some bills with Howlin’. It’s been an unexpected and joyful bright spot in an otherwise miserable year.

But each of you comes here each week for stories, opinion pieces, and Science Friday videos, and I don’t want the time that you took away from your loved ones to see what this email was about to go for nothing. So I have a Thanksgiving story for you. It’s a good one and fits the theme of family and friends for this holiday, but it does not have a happy ending. If you want to avoid a buzzkill (or are running out of libations), you might want to skip this one. It does not end well.

Last week, I wrote about my time as a climbing guide for the David Lee Roth band in Just like living in paradise. That was a great time in my life, and I remember those days fondly. A decade later, after retiring from climbing, I took up music and professional sound reinforcement. The bands I was in never went very far, but my sound, stage, lighting, and studio company, 5.11 Jimmy Audio, was successful.

Over the lifetime of this business, about a decade, I accumulated around 500 production credits, many with well-known, award-winning artists spanning genres from rock to jazz to classical to dance. It was a hoot. There is nothing wrong with hanging out with Benny Green after a show, having Eileen Ivers ask you to take a bow from the production riser at a sold-out St. Patrick’s Day event, or having Moses Pendelton ask if you wanted to fly to Italy to work on a show.

One of the greatest things about pro sound is the connections that you make with others. I remember having a dozen of the best live mix engineers in the world in my Idaho living room one night in the late 1990’s. A musician friend of mine from back east called during the party, and when I told him what was up, he asked me to ask if anyone at the party had ever heard of the engineer that used to tour with them back in the 80’s when they opened for Head East. I told him that I’d hand the phone to a guy who would know, since it was him.

To me, that’s always been a lodestone: the opportunity to create or be involved in special and unforgettable moments. I’ve had more than my fair share. How cool is it that you can hand a phone to a person in your living room that you just met, and they reconnect with an old friend across a gulf of thousands of miles and several decades?

I just wish that all unforgettable moments were good ones.

A few years after this, I got a call from a producer down in LA who wanted to book some studio time at my place in Idaho for an artist he was working with. My rates were cheap compared to LA, and Idaho is a nice place to hang out for a few weeks. I did pretty good business creating demos and rough mixes right along this line for a few years. This particular artist had some local connections and was bringing in some local talent to record backing tracks.

This was hardly ever a good thing. Locals from small Intermountain West towns hardly ever possess either the chops or professionalism to work efficiently in a studio environment. But as long as the checks cashed, it was the artist’s money.

The first day of this particular session, a vintage VW Beetle, complete with a rack and surfboard on top, rolled into my lane at 5200’ of elevation. You can, it turns out, take the artist out of LA, but you can’t take LA out of the artist. A van full of instruments from a nearby backline company came next, and then a nondescript mid-sized sedan arrived with a massive electronic stage keyboard that must have weighed 80 lbs. in the back seat.

I watched the driver of the car struggle to get the keyboard out and hoist it up onto his back to carry it into the studio while the passenger did what appeared to be Zen breathing exercises. After the keyboard was setup, the driver/roadie announced to the rest of us that he’d go fetch “Rock and Roll Steve” so that the session could start.

I had no idea who Rock and Roll Steve happened to be. I just assumed that everyone in the studio was a local music store teacher that had been hired to do the session. But Steve made a magnificent rock star entrance. I didn’t know who he was, but he sure didn’t make his living giving piano lessons at Mike’s Music.

The session went about the way that I thought that it would. As an engineer, it wasn’t my job to judge anything (unless asked, which this producer did not), just to help them achieve the sound that they were looking for. As the session wrapped for the day, Rock and Roll Steve asked if it would be OK if he stayed a few extra minutes to work out a part. I assured him that would be just fine.

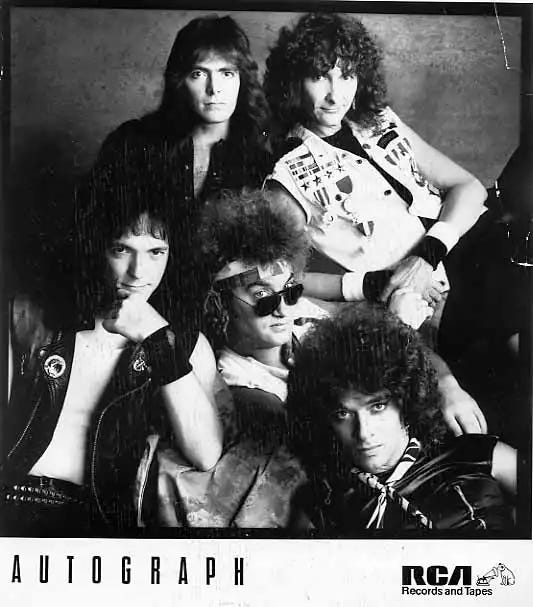

RRS looked vaguely familiar to me. I was sure that I’d seen him somewhere before, but I could not put my finger on where. As I went to fetch some cold beverages, his assistant walked with me, chattering about the session. “Man, Steve’s still got it—he sounds just like his Autograph days.”

Then it hit me—that is Steve Isham, keyboard player of Autograph, best known for the 80’s anthem Turn Up the Radio, from the album Sign in Please. I went to my record collection and got out my vinyl copy of Sign in Please to verify from the group photo on the back cover that it was indeed Steve Isham sitting a few feet away drinking a Pabst Blue Ribbon beer.

I wore out the dashboard in my 1984 Toyota SR5 truck, beating time to Turn Up the Radio back in the day. It’s an awesome song. And the keyboard player was sitting a few feet away from me.

When I sat back down at the rack containing all of the ADAT machines, Steve looked up and spoke directly to me for the first time all day. “I take it that some of the tracks laid down today did not meet your approval?” I was embarrassed that it showed, but he was right—the principal guitar player, in particular, was just not up to the task. Noticing the rack of guitars that belonged to me, he suggested that I pull one out and jam with him for a bit.

This might have been one of the most magical moments of my life. We hit it right off musically. I still have the tapes from the session, and I’m still blown away by how Steve, who could not read a note of music, was able to improvise wonderful harmonic and melodic content on the keyboard over a series of modulated ii-V-I guitar progressions. It gave me chills that day. It still does.

Steve and I were tight from that day forward. At his insistence, I was not only the engineer but a guitar player for the rest of the session. It was another of those moments when you feel 10 feet tall. I discovered that Steve was originally from the Pocatello area and had recently returned to live with his aging parents. We became fast friends. Hardly a week went by that Steve and I didn’t spend the better part of a night in a local bar drinking beers and talking music.

I was still teaching at the local university in those days, and one of the classes I taught was an orientation class for incoming students. I was a big fan of bringing in guest speakers. When I put the idea to Steve, I almost had to tie him down to prevent him from running over to the classroom building a few days early.

On the day of his talk, I had him meet me in the foyer of the classroom building so that we could walk to the classroom together. As we walked through the building to the classroom, I filled Steve in on student expectations for invited speakers. It was more of a monologue than a discussion, and I was still talking when we entered the classroom. I entered by myself, as it turned out, because Steve had paused in the hallway in order to make a rock star running stage-style entrance as I introduced him.

The students were blown away. It was a wonderful day.

But Steve had a drinking problem, and as the years passed, Steve’s problems with alcohol, which had been an issue for decades, became worse. I started feeling guilty about buying rounds during our weekly bar sessions. Steve could tell stories, play keys, and sing like an angel until that third or fourth beer, or the second shot, whichever came first. After that, it was a problem. And we were occasionally asked to leave drinking establishments.

Steve never got along with his Mormon parents, who disapproved of basically everything that he’d ever done. After a few years of living with them in Pocatello, he was asked to leave. Lacking anywhere else to stay around here, he went back to LA, hoping to find work in what turned out to be the final years of his life.

During this time, I was involved in club-level motorcycle road racing. I raced with the Willow Springs Motorcycle Club at Willow Springs International Raceway up near Rosamond, CA, an hour north of LA. On my once-a-month trips down to LA to race for a weekend, I’d arrange to drive down to LA either Friday or Saturday evening to meet with Steve.

Over the course of a few years of meeting Steve like this, I observed his circumstances deteriorating. He found little work and wore out his welcome with most of his remaining friends in LA. His drinking was now out of control, and I can’t recall seeing him sober on any of these visits.

It bothered all of us, his circle of friends, that the same guy who’d once played in packed arenas around the world was now living out of his Toyota Camry, his last possession besides the clothes on his back, in downtown LA, with few prospects for a bright future.

The last time that I saw Steve in person was in spring 2007, when I met him at a coffee shop in Burbank. He’d been camped in the parking lot of the strip mall where the shop was located for several weeks. It was obvious from the look that we got from the manager on duty that Steve had worn out his welcome there as well. But we were seated, and I had my last long talk with Steve face-to-face over a hot meal—the first that he’d had in a while. What was said was between us, but it was sad.

When we were done there, I drove Steve to a nearby motel, paid for a room for a few days, and gave him a few hundred bucks in cash. As I was walking away, I turned one last time to see a completely beaten-down human being walking toward his motel room, clutching packets of crackers he’d taken from the restaurant. It’s something that I can’t un-see.

I didn’t hear anything from Steve for a few months, and I hoped that that might mean that he was doing better since he tended to call when he was down and out. Then I heard from a mutual friend, a producer in LA, that Steve was in Skid Row. And despite offers of help, he seemed determined to drink himself to death.

A few weeks later, Steve finally called. I assumed that he was blasted because he was crying into the phone from the get-go. He told me that hardly anyone would take his phone calls anymore, but he knew that I would because we were good friends. He told me that he needed to tell someone that he’d been diagnosed with cancer, had just a few months to live, and that he was scared.

I have to stop here for a few moments to collect myself because what comes next is painful.

I didn’t believe Steve. I thought that he was trying to soften me up so that he could ask for money. I was polite and sympathetic, but I wasn’t buying it. I was sure that it was an alcohol-fueled con. He cried on the phone for the best part of 45 minutes. I listened and offered sympathy and help, but if I’m being truthful, no compassion.

A few months later, on December 9, 2008, Steve died of cancer.

I will never forgive myself for that final phone call. It still occasionally keeps me up at night, all these years later. A friend came to me for help in one of the worst moments of his life, and I wasn’t there for him. I can never make that right.

Steve’s funeral was here in Pocatello a few weeks later at a Mormon church on the west side of town, just about this time of year. There were, perhaps, 20 people there. It rained all that day, and I fixated on the rivulets of water running into the hole in the ground where they lowered his casket. It was the perfect metaphor for how I felt inside. From Budokon to a lonely, rainy service in a nondescript cemetery in a small Idaho town. Infinite sadness.

Tonight, I am spending the first Thanksgiving here alone since the days when Steve and I were friends. I’ve always wanted to think of myself as a good person. But things like this put that idea in doubt. Maybe I am a selfish person. Maybe I do lack sufficient compassion for others. Maybe I have more than a few wrinkles in my karma that need to be wrung out before the great wheel in the sky takes me home. Maybe I have it coming. Maybe I should be glad that I get to pay now. I don’t know. But I need to think about it.

So while you are reading this, I’m going to go downstairs where my 1975 Kenwood stereo is located, take my signed vinyl copy of Sign in Stranger down off the wall, drop the record onto my Technics turntable, and blast some paint off the walls. Maybe I’ll hammer my conscience clean with 110 dB of brute force.

Here’s to you, Steve.

Associated Press and Idaho Press Club-winning columnist Martin Hackworth of Pocatello is a physicist, writer, and retired Idaho State University faculty member who now spends his time with family, riding bicycles and motorcycles, and arranging and playing music. Follow him on Twitter @MartinHackworth and on Substack at martinhackworthsubstack.com

Being friends with a con artist - which all addicts are - is never easy. And deciding when helping means holding them accountable is doubly tough.

A lot of people love you, Martin, and we always will. Don’t ever forget that.