What could possibly go wrong?

It's no surprise that things go sideways when you remove the guardrails.

I have always done things my own way—which not infrequently meant bass-ackwards. I am that guy. It’s gotten in the way of everything.

I’ve always wanted to know. At first I embraced the mountains because I believed that if one could solve their challenges, much would be revealed. Then it was physics, because I was certain that if one could solve nature’s most difficult challenges, all would be revealed. Now, late in life, it’s people. But I am, at least, much more realistic. All I’m now hoping is for anything to be revealed.

Figuring out people makes climbing seem like a cakewalk. Comparing the effort required to deal with quantum mechanics to the brute force required to deal with the human condition is like comparing a naked man to a freight train. So it’s been all uphill—high risks, low rewards, payoffs small and infrequent.

I’ve been put in my place. Nonetheless, I persist. My expectations vis-à-vis enlightenment have been severely tempered with the passing of time. But maybe this is the way that it had to be. Perhaps without the struggle, I wouldn’t be ready to understand anything that the great wheel in the sky sees fit to reveal whenever it’s damn well ready. In the meantime, I’m spitballing. All I actually have to share is my own confusion.

Perhaps I’ll consult ChatGPT for enlightenment.

About a year ago, I wrote a Substack piece, Suspension of disbelief (is required), in which I discussed the then just exploding problem of gambling in sports. What could possibly go wrong, after all, when, without improving the human condition, we condone what were once vices becoming habits? How did we so quickly reach the point where gambling scandals at the collegiate and professional levels have become weekly revelations—this despite wailing klaxons and warning signs brighter than a Class A star in place of the moon?

A big part of the problem with things like this is avarice. There’s only so much stuff to go around. Always has and always will be. The more stuff that one has, the easier it becomes to acquire more. Haves and have-nots. And the powers that be are typically not into any overabundance of sharing. It’s the oldest story there is. Just see the Old Testament for details.

I’ve long maintained that society’s interest in promoting social safety nets while ignoring the counterproductive social behaviors (like poor education, criminal behavior, drugs, gambling, etc.) that render them necessary has far less to do with compassion than steely-eyed awareness of the lay of the land. It’s far less complicated and significantly less expensive to salve human misery with social welfare programs and entertainment than it is to raise a police force sufficient to keep the hoi polloi at bay if they ever get savvy to the real con. It’s simply much easier to pacify the natives by giving them a few coca leaves to chew on.

Almost literally, in the case of the Sacklers.

Now I know what some of you out there of the pile-on-in-the-comments persuasion are thinking. Has Hackworth fallen to the dark side of the Force and become a socialist? Nope. Fear not, mis amigos/amigas, I’m still down with good old-fashioned capitalism—as long as the game isn’t rigged, which all too frequently is not the case. My complaint starts when the playing field isn’t level.

End of gratuitous rant.

In recent weeks, sports fans have witnessed two major scandals involving illicit betting. Par for the course, the participants in and beneficiaries of these schemes were well-to-do athletes and criminals, while the victims were schmucks who imagined that sports betting was on the up and up (or didn’t care as long as they got paid).

It is noteworthy that until recently, those championing legal sports betting swore their most solemn oaths that legal gambling out in the open would allow for sufficient scrutiny to prevent the integrity of these sports from being called into question. How’d that work out?

For decades, colleges and professional sports franchises, in the interests of integrity, opposed attempts to legalize sports betting at the federal level. Then, a 2018 Supreme Court decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association overturned the federal ban on sports betting. The high court’s 6-3 ruling struck down a 1992 federal law, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, that had banned betting on sports in most states. The court’s majority opinion was that PASPA violated the 10th Amendment, which protects states’ rights.

That decision paved the way for an explosion in legalized sports betting—now a multi-billion dollar industry. So now, in a remarkably short amount of time, the real-world consequences of a decision in an arcane legal argument have been revealed.

To wit, this week, more than 30 people, including two NBA players, an NBA coach, and two MLB pitchers, are alleged to have been involved in criminal schemes to rig sports bets with organized crime. Say it ain’t so!

As I read the headlines concerning this, I could not help but remember the moment a year ago when I came across the news of Pete Rose’s passing on ESPN, with anchors discussing Rose’s ban from baseball as an ad for the network’s gambling app scrolled across the chyron at the base of the screen. That’s some brass for you right there. Just not, I’m quite sure, of the good kind.

The 2018 PASPA decision happened at about the worst possible time, being closely followed by the COVID pandemic and its associated lockdowns, which hammered all entertainment, including sporting events. It didn’t take long for sports leagues at all levels to not only tolerate but embrace legalized betting and the reams of money it brought into coffers laid bare by COVID.

Once the money train got rolling, there was no stopping it. The Raiders and A’s committed to Las Vegas. Most of the local sports viewed on TV began coming from networks controlled by gambling interests. The gold rush was on.

And, most ruinously, prop bets became a thing.

Proposition bets allow bettors to wager on not only the outcome of a game or the point spread but on outcomes at a granular level: a shot, a field goal, a hit, a swing, a pitch, a penalty, etc. Since prop bets are based on the results of individual effort, something that is very difficult to police, they are ripe for abuse. Unless a very unusual pattern of betting is detected on an individual prop (which is how the principals in the current scandals were caught), it’s all but impossible to discern between a simple swing and a miss or malfeasance.

Unless prop bets are eliminated, something that seems unlikely in the current regulatory environment, collegiate and professional sports seem headed to the same level of spectacle as professional wrestling. And why not? The WWE doesn’t seem too hard up for either money or fans.

If you convince most college trustees and professional sports franchise owners that they can make more money with Steve Austin and The Undertaker squaring off against each other in an at-bat than with Steve Carlton facing Tony Gwynn, it’s a matter of time until World Series rings become belts adorned with buckles the size of Texas.

Now, before you haters get spun right off your gyroscopes about some fancy-pants writer dissing the WWE, there’s something you should know. I was once a part of a fledgling tag-team wrestling duo known as “The Boone Hollow Boys.” We were hillbillies, complete with coonskin hats. Take that hate and stick it where the sun don’t shine, Gumby.

This ultimately unsuccessful but colorful bit of personal history came about due to my friendship with Lanny Poffo, aka “Leaping Lanny,” and Randy Poffo, aka “The Macho Man,” Randy Savage, both of whom I met by working out at a gym every morning at around 6 am during the early 1980s in Lexington, Kentucky. One of the headquarters of pro wrestling back in the day.

At that time, Lanny was as famous as Randy. They were quite the pair of entrepreneurs—and always willing to involve friends and acquaintances in money-making schemes. They were as good-natured as they come. I genuinely liked them both. I still miss Randy every day.

One of the first schemes Lanny tried to involve me in was TV evangelism. “Auspicious outcomes,” he claimed. “All of the money, none of the hospital bills.” That part of pro wrestling is real, by the way; it’s not stunt doubles jumping off those ring ropes.

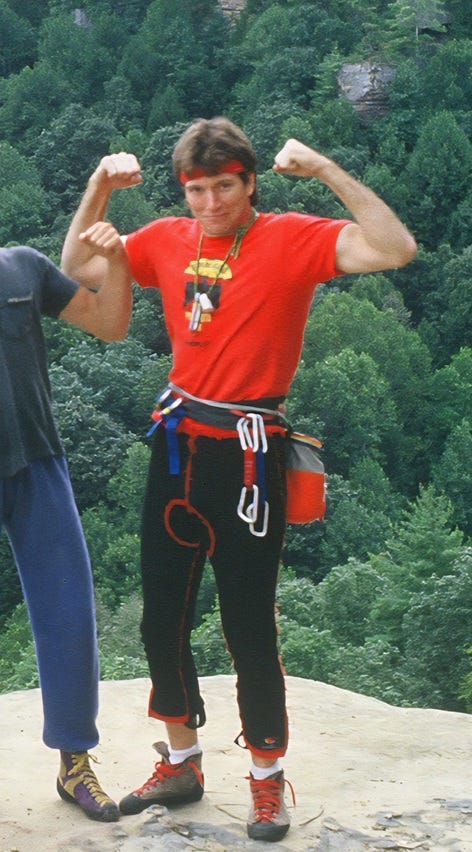

But young and inexperienced as I was back then, even I had my standards. TV evangelism wasn’t going to fly. So the next best scheme was to become a cannon fodder opening act for pro-wrestling headliners as they plied their trade in gyms and civic centers all over the Midwest. I lasted about one training session before I concluded that soloing hard rock climbs without a rope had more auspicious outcomes than ten minutes in a ring with guys big, strong, and agile enough to throw me into the next time zone.

So you’ll get no slagging of pro wrestling from me. I still remember deadlifting with Randy once, and he bested my personal record of 595 lbs as casually as lifting a bag of groceries for Karen Carpenter. Massive respect. Honest and no lie.

Pro wrestlers are not the issue with wrestling. It’s the people who think that wrestling is an actual competition, as opposed to athletic show business. And there are about to be a lot more of these unless we figure out a way to clean up betting in sports.

Associated Press and Idaho Press Club-winning columnist Martin Hackworth of Pocatello is a physicist, writer, and retired Idaho State University faculty member who now spends his time with family, riding bicycles and motorcycles, and arranging and playing music. Follow him on X at @MartinHackworth, on Facebook at facebook.com/martin.hackworth, and on Substack at martinhackworthsubstack.com.