Grade inflation is only a small part of what's gone wrong with education in America.

Actually, Kim Kardashian DID fail the bar exam, not the other way around. That's a win.

I came across a piece in The Washington Post a few days ago, “How the bar exam failed Kim Kardashian,” by Max Raskin, an adjunct law professor at New York University. The following is my favorite part of this comically misguided piece (emphasis mine):

“Many empirical studies question the effectiveness of the bar exam in predicting lawyerly prowess, but this should be settled by a free market. We don’t make auto mechanics or electricians go to school for an additional three years, even though their professions can cause much more physical harm. We rely on credentials, social signaling, reviews and other market mechanisms for determining quality.

Lawyers are not doctors, so more experimentation in the legal profession can be tolerated. Lawyers are not constantly making life-or-death decisions, and when they do, there are procedures to ensure that counsel is competent.

Explain that to anyone currently incarcerated in our best-of-all-possible penal systems because they received a first-rate vigorous defense from some mental Godzilla of a public defender. The best adjustment to Raskin’s karma over his thesis might be to lock him up for a few days at Riker’s Island and have him explain to his cellmates how even less competent attorneys would have been a good thing for them.

Retorts, as you might imagine, have been as strident, vociferous, numerous and as thoroughly pleasant to observe as a sunny verdant field after a long winter. But my favorite, a brilliantly succinct response for such a masterpiece of sophistry, was right at the top of the comments section: “I’ve heard lawyers talk. The bar exam needs to be twice as hard.”

Raskin’s spectacularly tone-deaf pontification had the misfortune of arriving at just about the same time that people have started questioning why the average grade in undergraduate classes at many leading universities is an “A.” That happens to be a really good question.

American education, from kindergarten all the way through higher ed, extant, has been, for decades, in decline. I’m not just opining here either; I’m quoting. This has been a matter of contention among in-the-trenches academics all the while, but not so much among education researchers, school administrators and politicians, who, for various reasons all linked to self-promotion, claimed that declining metrics meant that the standards they were supposed to gauge must be wrong.

It wasn’t the participants, according to the education mafia, it was the system itself. If eighth graders are unable to pass algebra at the rate required to keep them happy, their parents happy, and everyone attached to the college pipeline spigot happy, there must be something wrong with algebra.

Perhaps algebra is intrinsically unfair. Perhaps algebra just isn’t relevant enough for students to self-actualize the Zen required to solve for x in the 21st century. What it cannot possibly be, according to the paradigm in what passes for research in education, is lack of preparation and/or motivation. That would require legions of advanced degree holders to admit that they fucked up. Don’t hold your breath.

To wit. Back in 2015, San Francisco officials famously removed algebra from the middle school curriculum based on concerns surrounding social equity promoted mostly by one scholar, Jo Boaler, whose research on this topic at Stanford University was recently the subject of a 100-page complaint citing over 50 instances of misconduct in her research citations. As it turns out, ideology, masquerading as research, was used to deny San Francisco middle school students access to the pride of Babylonia for nearly a decade.

This is, as you may suspect, a recurring theme in the collapse of education in America. Throw in a dollop of insufficient parenting, another topic entirely, and you have the perfect storm.

Like the proverbial frog in a pot of boiling academic stew, it was easy to ignore arcane disputes that shaped educational policy in this century as the failures piled up until 2020. COVID revealed, as unmistakably as oncoming high beams on a dark highway, numerous failings in education.

Curiously, during this same period, vast advancements have been recorded in every human endeavor where performance can be objectively measured over time—athletic ability, wealth, health, and longevity. Education stands out as the only exception. Though I have raged about this many times, I have not yet begun to fight.

At a time when we ought to be raising educational standards as the result of advances in the breadth and depth of knowledge and how efficiently it’s now possible to share, we are, in fact, lowering standards, à la Boler. We’ve had to redefine what constitutes merit across the board in America because our system of education, upon which a lot of things hinge, has failed to produce meritorious outcomes.

Yesterday, I had a short back-and-forth with fellow Substacker The Ivy Exile1 about declining standards in AP (advanced placement) courses. In almost a quarter-century teaching university physics, only twice was any student who’d taken AP physics in high school able to pass the very basic exam we gave to determine if we’d allow the AP credits they’d earned to substitute for our courses—and both of those students were savants who’d taken graduate-level optics and astrophysics courses from me before they could legally drive a car.

AP students are supposed to represent the crème de la crème. Yet I found most of them to function much more reliably as weather vanes for the katabatic winds sweeping through education. If the best students knew so little, how bad was it further downhill?

Pretty bad, as it turns out.

Current educational standards simply aren’t what they used to be. As mentioned above, the average undergraduate course grade these days is an “A” in many top universities. This seems pretty ridiculous to anyone over 40 who’s spent much time around any classroom (even journalists and TV presenters). “Grade inflation” is suddenly on everyone’s radar.

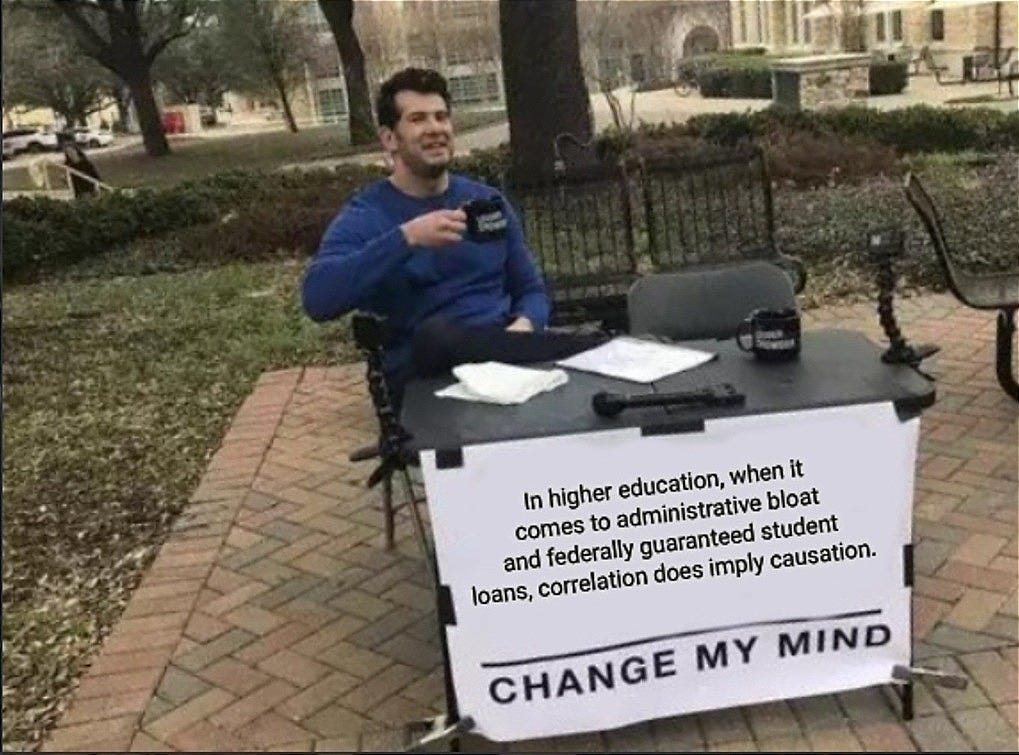

Grade inflation, in my reckoning, first became a nationwide issue around 1980—about the time that Pell Grants were established and that colleges began pushing guaranteed student loans, rather than work-study or apprenticing programs, to finance the cost of higher education. This also corresponds, mirabile dictu, with the beginning of the explosive growth of administrative ranks throughout education.

Once the glut of administrators began to descend like locusts on education, schools had a lot of well-compensated non-faculty employees with a vested interest in keeping happy students in seats. At that, at least, they proved exceedingly competent and inventive.

During my last decade in higher ed, I taught several large sections of introductory astronomy, which counted as a general science elective. I was responsible for somewhere between 200 and 400 students every semester in this course. It was one of my university’s most popular courses.

Except for one thing. My average grade was not an “A.”

The first time I got called into the dean’s office to discuss my grading policy, I thought it was a joke (it was not). That same semester, the teacher of the year award in the College of Science and Engineering went to a chemist who allowed students in general chemistry to take any exam as many times as they wanted to improve their score—the exact same exam. The writing was on the wall. I was a short-timer in such a ludicrous system.

Take that affront to maintaining standards, multiply it by the number of educational institutions in the USA, and you can begin to ascertain the extent of the problem. In a system with no evident standards, scant acknowledgement that things of substance are generally not easily learned, nary a hint of the importance of discipline or any emphasis on developing a work ethic, and every financial incentive to give students what they want instead of what they need, it’s not overly difficult to see how we got where we presently find ourselves—in the crapper.

This is an obvious segue back to the lede. The bar, in fact, did not fail Kim Kardashian; she failed the bar. I count that as a win. After serving as an expert witness for several decades, I, too, have heard lawyers talk. That freaking exam needs to be about a hundred times harder.

Associated Press and Idaho Press Club-winning columnist Martin Hackworth of Pocatello is a physicist, writer, and retired Idaho State University faculty member who now spends his time with family, riding bicycles and motorcycles, and arranging and playing music. Follow him on X at @MartinHackworth, on Facebook at facebook.com/martin.hackworth, and on Substack at martinhackworthsubstack.com.

The Ivy Exile, aka J.A., is a gen-you-wine academic blue blood bereft of as much as a scintilla of bullshit concerning his worth-your-while-to-discover views on the Ivy League. His pedigree is impressive, if you overlook the occasional poor choice of Substack associates. It’s evidently a long way downhill after Bill Moyers. On the name thing—I just can’t figure out if he wants to remain incognito as The Ivy Exile (make sure to capitalize that “T”) or go by his actual name. Out of respect, I’m playing it safe. Not respect as in, “I’m worried about a guy who went to a school where they had rowing and croquet instead of football,” but respect as in, “These NYC guys all know someone who’s connected.” Salute!

In the name of helping students, these supposed "progressives" undermine the kinds' very futures. When my Mom graduated high school in 1956 - HIGH SCHOOL - she could read and write French, Latin and ancient Greek, do calc, and had read most of the literary classics. And she wasn't even top of her class!

Your quip in the footnote about the Ivy Exile - I went to a school where more people turned out for tennis than football. It was hilarious (both visible from my dorm room balcony). Being Texas, even more hilarious was the roars you could hear a ways away from the stadium where high school football was played. Anyway, the school then decided that football was better for its image than tennis (at which it actually fielded a team of some note, interestingly, a significant number coming from South Africa, much like Elon Musk except much more tanned and athletic) so it pretty much defunded its tennis program in favor of football. In retrospect, perhaps that was the beginning of the long slow march downwards, because some years later I opened my alumni news to find that they were offering a base level course to teach general chemistry math. So much for what we called "baby calculus" being the base level course (the expectation for those enrolled in regular freshman level science courses was that you were underway in the regular calculus sequence...), with those enrolled in the even lower level trigonometry the mathematically hopeless liberal arts majors who couldn't even make that cut but must have a math credit of some sort. Oh well. Last time I picked up on the annual fund drive phone call, I had a lovely chat with the friendly student calling, gave all sorts of advice and helpful hints, and then at the end declined to give anything.